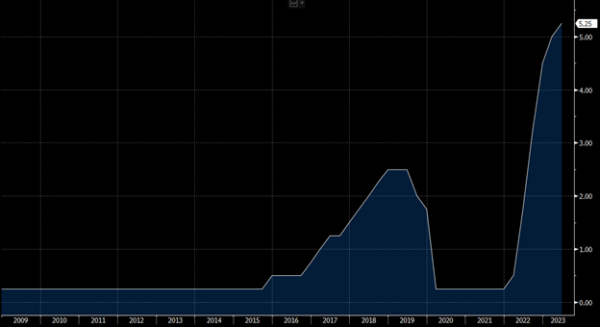

The current interest rate cycle has been one for the record books. If I told you at the beginning of 2022 that we would see 10 consecutive rate hikes that would bring the Federal Funds Rate to 5.25%, would you have believed me? After experiencing an ultra-low interest rate environment for most of the past 15 years, the band-aid has been ripped off and we have seen rates skyrocket. This may be one of the fastest rate-hiking cycles in history, but how does it compare to the prior cycle?

Considered the most significant downturn since the Great Depression, the economic downturn beginning in 2007 (the Great Recession) facilitated what would become a long era of low interest rates across the world. Throughout 2007 and 2008, the Federal Reserve cut the overnight borrowing rate from 5.25% all the way down to 0.25% to ease monetary conditions in the economy.

As the economy began to fold due to a collapse of the U.S. housing market, extreme strain was placed on the financial system and the Federal Reserve attempted to free up liquidity in the economy. Additionally, $7.7 trillion of quantitative easing and $787 billion of spending in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was injected into the financial system to reduce major losses in financial institutions and large corporations.

Federal Funds Rate 2009-Present

Source: Bloomberg

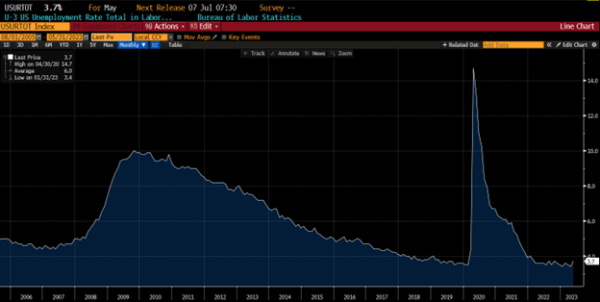

With these fiscal and monetary policies in place, the recovery began after seeing unemployment finally max out at 10% in October 2009. Unemployment did not fully recover to 5% until 2015. Meanwhile, the Federal Funds Rate was still at 0.25% through this entire period.

It was at this point in 2015, when the Federal Reserve believed that the economy was in full swing and that rate increases were necessary. Over the next four years, rates increased from 0.25% to 2.50% by 2019. For those of you keeping track at home, it took the Federal Reserve 10 years to reach their terminal rate during the prior interest rate cycle. Historically, the average tightening cycle has lasted 21 months with a total Federal Funds increase of 3.02%. The tightening cycle following the Great Recession lasted for 36 months and saw an increase of just 2.25%. This specific tightening cycle lasted longer than average, and rates increased less than average. Keep this in mind when we examine the current cycle.

We began to see modest rate cuts in the second half of 2019 as the economy began to get frothy. In an effort to make liquidity a little bit more restrictive, the Federal Reserve cut rates three times in the second half of 2019. At this point, the overnight borrowing rate was 1.75% and the Federal Reserve decided to pause rate cuts until an unforeseen catastrophe would change that. Fast forward to March of 2020 and the COVID-19 virus caused statewide shutdowns combined with social distancing measures that resulted in a severe economic downturn.

Once again, as history repeats itself, over the course of one month the Federal Reserve cut the overnight borrowing rate back down to zero to stimulate the economy. In addition to monetary policy, the U.S. government injected over $2.2 trillion into the economy in the form of individual stimulus payments under the CARES Act. This time around, a major difference has appeared during recovery…inflation.

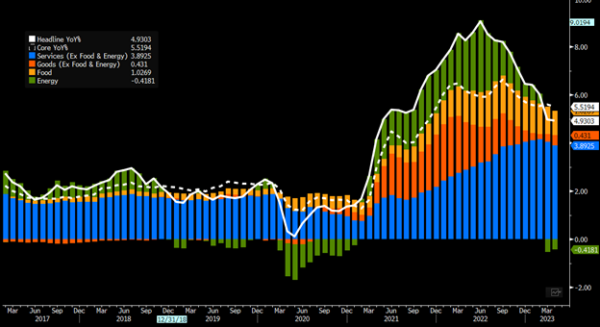

Consumer Price Index (CPI) YoY

Source: Bloomberg

High inflation is generally characterized by a sustained and significant increase in the overall price level of goods and services within the economy. How did we follow up an economic downturn with “runaway” inflation? One factor that can contribute to high inflation is excessive monetary growth. If the money supply increases at a faster rate than the growth of goods and services in the economy, it can lead to an imbalance between supply and demand and drive-up prices.

Throughout 2021, we had heard from the Federal Reserve and the political administration that inflation was transitory. They described this period as higher-than-normal prices due to the COVID-19 crisis that would soon revert to normal. After slashing rates to zero to aid the economy, the Federal Reserve adopted a new monetary policy strategy in late 2020 to let inflation run hotter than its long-term goal of 2% a year. As 2021 showed an ease in COVID-19 policies with the vaccine, the economy started to reopen while supply chain bottlenecks started piling up everywhere.

With all these factors coming together, between thousands of dollars in direct stimulus payments to tens of millions of Americans throughout 2020 and 2021, we started to see broad-based price gains throughout the U.S. economy. How could inflation become transitory with prices rising, supply chain bottlenecks, cheap money, and an influx of stimulus flowing into the economy?

In the spring of 2021, the Federal Reserve was forced to confront the problem of high inflation. Annual CPI inflation remained around 5.3% through September 2021, before jumping to more than 7% by December. Six months later it would be more than 9%, a four-decade high. As inflation continued to rise throughout 2022 so did wages, which additionally increases inflation. During this time, inflation adjusted earnings were down 3% compared to this time last year.

Source: Bloomberg

To put this in perspective, the Federal Reserve raised rates 500 basis points in about 15 months as inflation rose 800 basis points in the same period.

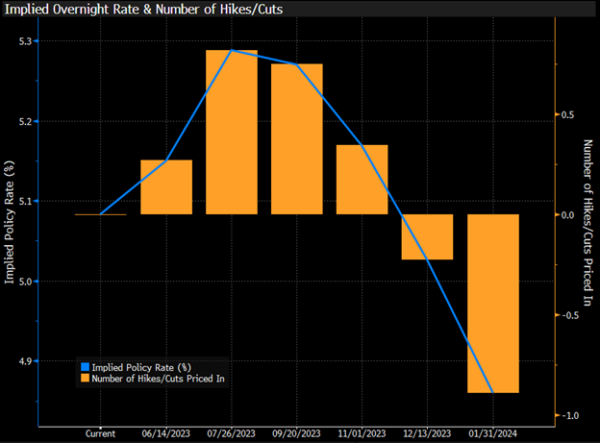

Now that we know the current economic environment and what the Federal Reserve did to combat it so far, what’s next? We do not have a crystal ball and after the last rate hike the consensus was to pause rates for the better half of the year and possibly see a decrease in rates towards the later end of 2023 and into 2024.

Currently, inflation is sitting around 4.9% which is still higher than their target rate of 2% and this seems to be the focal point of the Federal Reserve’s decision making.

What are the biggest factors the Federal Reserve considers when raising rates?

- Inflation rate.

- Unemployment rate: A low unemployment rate suggest tight labor market and potential upward pressure on wages, which could lead to inflationary pressures.

- The economic growth rate: The Federal Reserve wants to keep the economy growing at a moderate pace and this is indicated by GDP.

- Economic risk: Considerations include things like a recession, a financial crisis, or a natural disaster.

Where does the future of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decisions sit? As stated, their focus is to lower inflation and avoid putting the economy into further economic risk. This contradicts their other two targets of low unemployment and economic growth because with higher employment and economic growth with high inflation causes more inflation.

The Federal Reserve certainly has their hands full and is still signaling to keep interest rates steady in June 2023 while retaining the option to hike further in coming months.

Source: Bloomberg

About the authors:

Nick Meletio

Nick Meletio is senior vice president at UMB Bank, n.a. Capital Markets Division. He is responsible for investment portfolio strategies, fixed-income securities selection and asset-liability management.

Tyler McAllister

Tyler McAllister is an investment officer at UMB Bank, n.a. Capital Markets Division. He is responsible for helping institutional clients understand how to best manage their bond portfolios and interest rate risk.

Learn how UMB Bank Capital Markets Division’s fixed income sales and trading solutions can support your bank or organization, or contact us to be connected with a team member.

Disclosure:

This communication is provided for informational purposes only. UMB Bank, n.a. and UMB Financial Corporation are not liable for any errors, omissions, or misstatements. This is not an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument, nor a solicitation to participate in any trading strategy, nor an official confirmation of any transaction. The information is believed to be reliable, but we do not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Past performance is no indication of future results. The numbers cited are for illustrative purposes only. UMB Financial Corporation, its affiliates, and its employees are not in the business of providing tax or legal advice. Any materials or tax‐related statements are not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used or relied upon, by any such taxpayer for the purpose of avoiding tax penalties. Any such taxpayer should seek advice based on the taxpayer’s particular circumstances from an independent tax advisor. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the opinions of UMB Bank or UMB Financial Corporation.

Products, Services and Securities offered through UMB Bank, n.a. Capital Markets Division are:

NOT FDIC INSURED | MAY LOSE VALUE | NOT BANK GUARANTEED